Talking with different people I got a lot of questions about what it was like to travel during a worldwide pandemic. Here are my impressions from an international travel in time of Covid-19. Briefly, we have traveled about 12,555 km (7,800 miles), got seven negative Covid-19 test results, stayed in quarantine hotel for 10 days, took six planes and roundtrip 14-hours boat ride, experienced extreme weather with temperature as low as -27°C (-16°F), strong wind about 35 km/h (22 m/h), zero visibility due to wind-driven snow, and rough landing at crosswind in Atlanta. We even tested gender-oriented coats designed for polar regions by Russian company BASK.

On March 12th we were released from the quarantine hotel and after two Covid-19 tests we boarded a plane to the island of Spitsbergen in Svalbard archipelago, which is located between mainland Norway and the North Pole

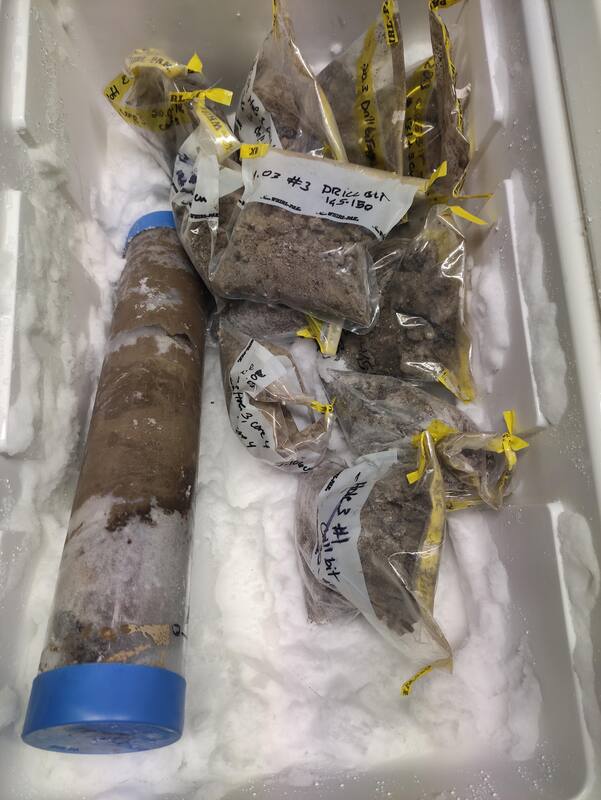

The team cored active layer and permafrost from a few locations around Ny-Ålesund. Samples from five shallow and 3 deeper boreholes with the total length of about 10 meters were collected and transported to the University of Tennessee Knoxville. Our travel back home was shorter, just four days. Even it took a whole month of March to get field work done, I have a feeling that time in Svalbard flew by incredibly fast.

0 Comments

AMP'D Blog: Katie Sipes - Lessons from the field: the hardest person to convince is yourself4/20/2021

This trip taught me to speak up and believe in your own abilities. The permafrost drill and all the metal rods and barrel broke. I pondered if I should share that I know how to weld, which could fix the items. I didn’t want to seem like I was bragging or talking about myself too much. After everything was certainly broken, I had to share. Welding actually fixed it- not by me, but by the generous wizard that works in Kings Bay’s shop. Maybe if welding hadn’t been brought up we would have stopped drilling.

In Ny-Ålesund, the residents are mainly Norwegian, and therefore speak Norwegian. Which is mutually intelligible with Swedish and Danish* (kinda). I’m a self-taught Swedish speaker and can get around until I need to show my American passport. Turns out, most of the residents thought that I was fluent Swedish and wrote me off as a Swede. I was speaking (in Swedish) to the chef, telling her that all the food she made was amazing and that she was so kind. She then says, “sorry, I don’t know that much Swedish.” I was floored ‘HAH, me neither’, I thought. But when you commit, and speak the sounds and listen then the brain fills in the rest of the sentence/meaning == boom, passable Swede. I want to be an astronaut. This is not a childhood dream, but a more recent realization that I could actually be an astronaut- so let’s go for it. Because of this goal, I love all things NASA. The first day we were in Ny-Ålesund I looked out the window and saw a NASA equipment container. The chances of my favorite thing being in my favorite place - I was gobsmacked ! Especially because the USA doesn’t have a research station in Ny-Ålesund. I laughed so hard I shed a tear. The universe has a strange way of reassuring us. Imposter syndrome is a bitch. Most of all, I learned that I can (and should) learn from anyone willing to teach me. I need to remain humble but give myself credit. I hope these lessons help someone struggling with imposter syndrome or, at least, give them the solace that we all feel it and the gumption to believe in themselves. And certainly, fake it till you make it. One thing I love about field work is that no matter how many fancy degrees you have, no matter how smart you think you are, nature will find a way to lay you low. This permafrost drilling project was no different. We figured the rocks would be our downfall. But it was metal that took us down in the end. Despite having worked on permafrost in the past, I had never actually drilled into permafrost myself. So, I went with Tatiana Vishnivetskaya and Andrey Abramov, my well-seasoned permafrost scientist colleagues, to do reconnaissance in the summer and try to anticipate any problems that would arise when we did the real drilling under snowcover in the early spring.

So, we scoured the new wonderfully detailed geological maps made by the Norwegian Polar Institute at night and picked out sites that might have deeper soil depth for the next day.

We spent the rest of the day trying to troubleshoot the problem of the sheared screw. Looking at the broken fragment seemed to suggest that the metal itself was bad and had failed even though it was not experiencing much torque.

We started the next day with high hopes at our second location, Kvadehuken, a starkly beautiful peninsula that apparently translates to “bad corner” from old Dutch. Here, we managed to drill down to bedrock past the all important 2 meters permafrost depth. Success! I did a full-on happy dance when we hit 2 m. That was the goal of the trip and we had achieved it. But, we were drilling in a shallow brine lake, so the cores were coming up wet, which is fairly dissatisfying when one is going for the frozen stuff. But I am told that it still qualifies as permafrost because it is below the freezing point of water. Whatever. I don’t make the rules. Karen delighted to reach the permafrost. Success! But to feel satisfied, we really needed something with rock hard ice in it. Something that looked like the permafrost of our dreams.

L-R: James Bradley, Donato Giovannelli, Karen Lloyd and Andrey Abramov.

Margaret writes a piece for the UK Arctic Office on the AMP'D project, which is published on their website today, and copied below.

We divided into a “drilling team” and a “lab team” with the drilling team focused on finding suitable areas near Ny-Alesund for drilling permafrost, and the lab team focused on sectioning permafrost cores and preparing them for future microbiological analyses in our home laboratories. Contamination is a central challenge for drilling any material for microbiology investigations, including permafrost. Often fluids are used to support the drilling process but using drilling fluids can contaminate permafrost with foreign microbes. Since our investigations focused on in situ microbes, avoiding contam-ination was essential. Avoiding contamination is particularly important when the abundance of microbes in the permafrost is low, which preliminary investigations of the microbiology of this area suggest. Con-tamination may obscure real microbial signals. Our drill did not use drilling fluids, and because of this, friction between the drill barrel (the rotating cylinder at the end of the drill that cut out permafrost core sections) and the surrounding permafrost created heat that could melt the permafrost. Preventing the core material from getting too warm during drilling was therefore also important. Permafrost core sections were removed from the earth in ~30 cm intervals in core liners that held together the structure of the permafrost. Varying with depth, the permafrost material was dry, loose, and sandy, and sometimes it was hard and consolidated like rock. Coloured layers could be seen at different depths of the core from the same borehole hinting that different layers have different geochemistry and different in situ microbial metabolisms. In the lab, we separated each core section into smaller sections so that specific permafrost layers could be analyzed for microbiology and biogeochemistry. The cores from each of these were stored frozen and transported to laboratories in London, Naples, New Jersey, and Knoxville, for experiments and analyses that will soon help us understand how microbes in Svalbard permafrost are affected by and participate in Arctic warming.

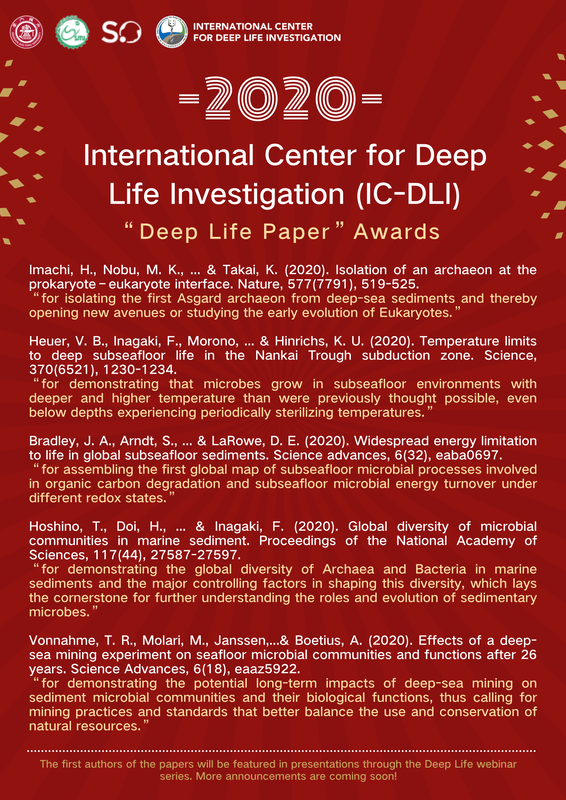

James receives the International Center for Deep Life Investigation Deep Life Paper of 2020 Award “for assembling the first global map of subseafloor microbial processes involved in organic carbon degradation and subseafloor microbial energy turnover under different redox states”, published in Science Advances, which was selected from among the most significant research papers of 2020 proposed by the IC-DLI community, based on novelty and potential for long-term impact. James will present the work in a forthcoming Deep Life webinar series.

|

Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed